2023-24 Season Summary

The Colorado Avalanche Information Center celebrated its 50th anniversary of operations during the 2023-24 season. This year we didn't make any major changes to our operations. This was the second year of using dynamic forecast zones and issuing avalanche forecasts in the afternoon.

We did some restructuring to our team to be able to provide better backcountry forecasting service. This season a senior forecaster was hired for the Northern and Central Mountains, a permanent seasonal forecaster was hired for each region, and four field technicians were hired (two each in the Northern and Central Mountains). The remaining positions will be filled in the summer of 2024 for the 2025 season. The addition of the field tech positions was a big change. These positions helped gather information in data-sparse areas. We also hired a Public Information Officer to coordinate communication.

Additionally, we launched the Avalanche Accident Explorer, an interactive map that displays information about Colorado’s fatal accidents, in collaboration with Colorado Mountain College. We also partnered with Simon Fraser University to launch The Snow Pool—a research panel to help inform our avalanche risk communication–and completed three surveys this season. And we started some initial work to communicate avalanche safety information to Colorado’s large Spanish-speaking population. Specifically, we created a Basic Avalanche Safety page in Spanish and translated educational videos which are now on their YouTube page.

Of course, the flow of the day-to-day operations remained centered around weather and avalanche cycles. This season was characterized by a slow start to winter, distinctive weak layers, numerous close calls—including one involving a CAIC forecaster–and several impressive successful companion rescues.

As of June 10, CAIC recorded 5,632 avalanches during the season. Two people were killed in two separate avalanches, four fewer than the annual average of six over the previous 10 years. We documented 120 incidents—a season record for CAIC—with 149 people caught in avalanches, exceeding the 10-year average of 80 incidents and 98 people caught. This included 18 avalanches where multiple people were caught.

The season got off to a slow and problematic start in terms of snowpack building. A storm in late October, which produced the season’s first avalanche cycle, was followed by a three-week dry spell. Lingering snow faceted and weakened on most northerly and easterly-facing slopes. A thin crust formed on the surface on many slopes, capping the faceted snow below. This crust-facet combination would become significant for avalanches in the second half of November and beyond.

A pair of storms in mid and late November built slabs on this weak base, developing an early-winter Persistent Slab avalanche problem. The second of these storms hit right around Thanksgiving and created the winter’s first CONSIDERABLE avalanche danger in parts of the state. These conditions resulted in the season’s first serious close call in the western Elk Mountains where four backcountry skiers were caught and three people partially buried, luckily with no injuries.

December started with a shallow snowpack comprised of faceted snow grains from top to bottom. Most areas lacked a cohesive slab required for large avalanches. The deepest snowpack was in between Crested Butte and Aspen, where SNOTEL sites showed the snowpack was only 80% of the 30-year median. In the rest of Colorado, this number was closer to 50%.

A large storm affected all areas of the state in early December. This big storm fell on a weak snowpack, creating a large avalanche cycle and our first Avalanche Warnings of the season. We saw a flurry of close calls during this period. This was followed by a long dry and warm spell that brought most mountain ranges to LOW avalanche danger. During this period, attention shifted from basal weak layers to surface weak layers as warm weather and cold nights faceted the surface snow and allowed surface hoar development. As 2023 rolled to a close, Colorado had zero fatalities at this point in the season–the first time since the 2018-19 season.

At the start of the new year, snow depths were well below normal throughout much of Colorado. Unusual for mid-winter, the statewide avalanche danger was LOW. Things changed starting January 4 when the month’s stormiest period began, doubling the snowpack in places as storms continued through January 18. This stormy period produced a spike in avalanche activity. Tragically, on January 22, near the town of Ophir in the San Juan Mountains, a solo backcountry rider was caught, carried, partially buried, and killed due to injuries sustained in the avalanche and environmental factors. The next rash of avalanche involvements occurred the weekend of January 26-27. Over these two days, four groups were involved in accidents, with seven people caught, five partial burials, and one injury.

January ended with a dry period that allowed persistent weak layers to develop in the upper snowpack across the state. Depending on aspect and region, it was either surface hoar, near-surface facets, or facets around a crust that developed on or just below the snow surface. The first February storm buried these weak layers and would become responsible for many close calls and a fatality near Crested Butte. Of note, the layer of surface hoar crystals was buried “upright” because this storm arrived with little wind, creating an especially fragile weak layer. Although the buried surface hoar was widespread throughout the state it seemed to be weakest in the western Elk Mountains. Avalanches outside of this area mostly failed on the near-surface facets and near-crust facets.

Four notable storms in February increased the statewide Snow Water Equivalent (SWE) close to 30-year median values, and then March pushed our snowpack to above median values. Snowfall was consistent in March, helping build a deeper and stronger snowpack.

There was a higher-than-usual number of people caught in avalanches during the last two weeks of March, with an average of 2 people caught per day. Miraculously, of the 32 people caught from March 17 to March 31, none were seriously injured. Most of these avalanches were relatively small but happened in steep, consequential terrain. Two people were fully buried in two separate avalanches that thankfully ended in successful life-saving rescues. Despite some very close calls, there were no fatal accidents in March for the first time since March 2020.

April delivered a generous amount of warm, sunny weather and three snowy periods. These small storms helped pump the brakes on an overall depleting statewide snowpack and an early start to the runoff season. Throughout the month, the primary avalanche concerns evolved from the long-standing Persistent Slab avalanche to a hodgepodge of wet snow and new snow hazards. This transition to more spring-like conditions inspired people to step out into bigger and more complex terrain with confidence. However, this is probably why we saw frequent spikes in reported avalanches each time it snowed. The places where we observed the highest density of avalanche-related incidents in April are the same places that received the most snow and the slowest to transition to more spring conditions.

There were numerous close calls in April, with multiple people caught and two incidents resulting in injuries. Of note, on April 8 a CAIC forecaster who was at work was caught and partially buried in an avalanche. CAIC staff followed all safety protocols. This incident highlights that even risk management planning does not eliminate the inherent risk of working in a backcountry environment. This is the most serious workplace accident we’ve had since 2014 when a forecaster was injured by an explosive detonation. We are grateful that our colleague survived this recent accident without life-threatening injuries. We always strive to learn from accidents and near misses, and that includes our own. Following this accident, we reviewed our field safety plan and our procedures and made adjustments to strengthen our protocols.

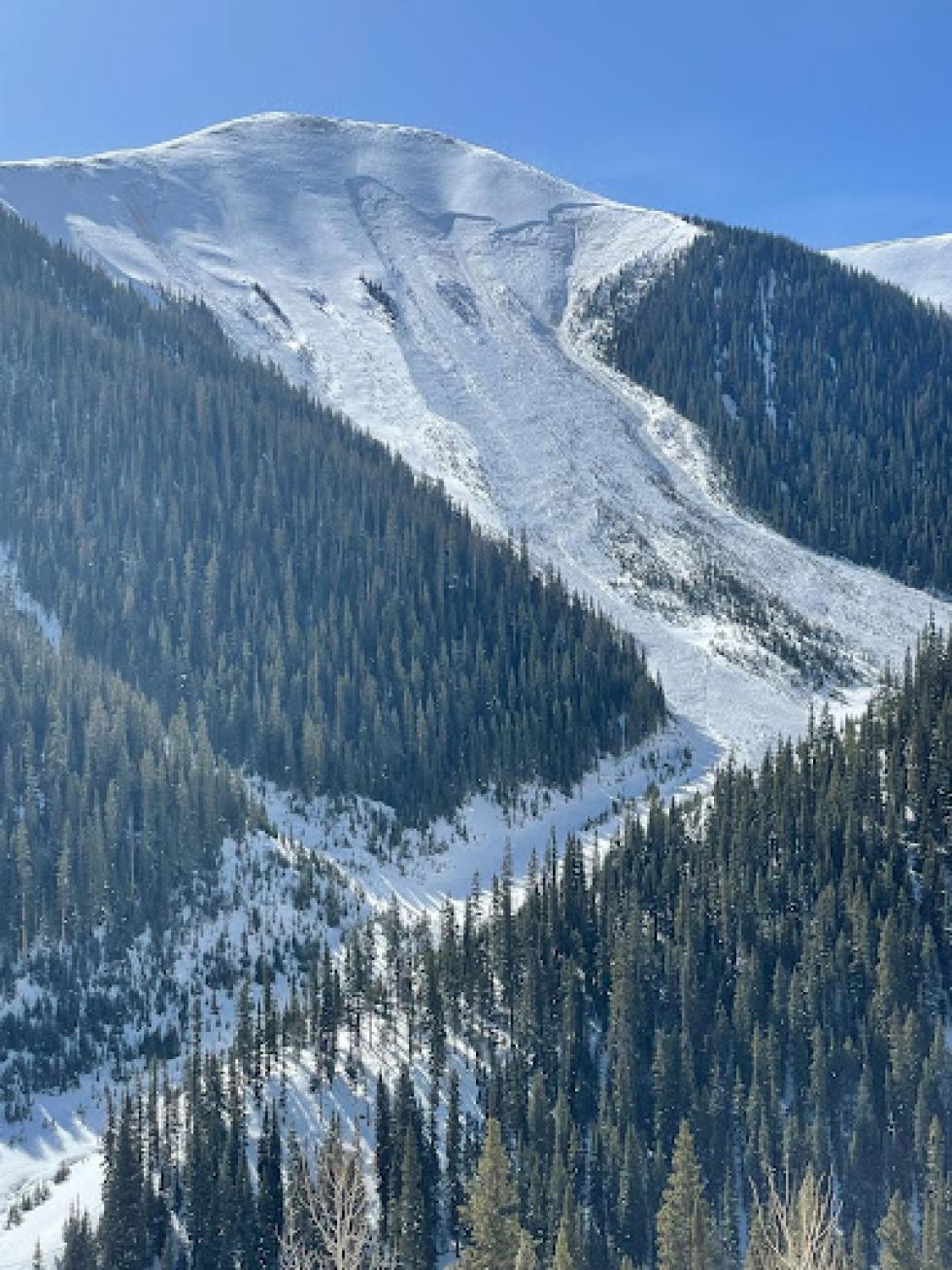

May saw less than half of the number of avalanches reported in April even as the month saw more wintry weather than usual. The stormy period between May 6-12 left areas in the Northern and Central Mountains with snow totals over two feet. Three of the five avalanche incidents in May happened on May 12. Not only were they on the same day, but all three were near Loveland Pass on wind-drifted upper-elevation slopes. The skies finally began to clear on May 12, allowing the sun to poke out. The new snow got wet, and a Loose Wet avalanche cycle began. Over the next week, daytime highs climbed, and overnight freezes became weaker. A Wet Slab cycle started on May 14 and peaked on May 19 with 26 total Wet Slab avalanches; 10 were large enough to kill or injure a person. Two final pulses of winter brought snow back to the mountains in late May.

In early June, a Special Avalanche Advisory went into effect for Colorado’s high country to warn about large and destructive wet avalanches and to flag that the conditions were not normal for early June.

We hope the number of multiple-involvement accidents is just an anomaly and not a sign of a worrisome trend, though this is the third year in a row with similar patterns.