The Danger of Improving Stability

by Brian Lazar and Ethan Greene

Santa delivered a lot of snow to Colorado in the past two weeks, just in time for Christmas. Have we been naughty or nice? Well riding conditions have been fabulous, but there have been some impressive avalanches.

The last storm brought significant snowfall and avalanche activity, but since then the snowpack has been getting stronger and we’ve seen fewer avalanches and less cracking and collapsing. Paradoxically, this does not mean things are necessarily safer for the backcountry traveler. The likelihood of triggering an avalanche is decreasing, but the size and consequences of avalanches that do release are steadily increasing. This trend has prompted discussions amongst our forecasters about whether or not we are moving into a new risk paradigm, and perhaps, a new avalanche problem: Deep Persistent Slab (DPS) avalanches.

DPS avalanches have many characteristics in common with Persistent Slab (PS) avalanches. Both break on persistent weak layers. You can trigger both remotely and from low-angle slopes. Both of these types of avalanches can fail in surprising ways, breaking across and around terrain features that would contain a Storm or Wind Slab avalanche. PS and DPS avalanches have a lot in common, but there are some very important differences that affect how we avoid them and manage our own personal risk.

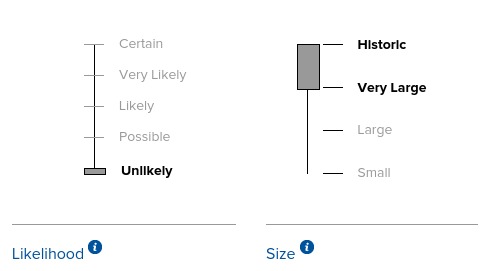

DPS avalanches are low probability and high consequence events. The likelihood of triggering a PS avalanche and the size of that avalanche can vary over a wide range. DPS avalanches are a specific creature, very large in size and hard to trigger. We look for three things before we add it to our list of Avalanche Problems. Those three things are:

- Avalanches will be stubborn to trigger, Unlikely or Possible on the Likelihood scale

- Avalanches will be destructive, D3 or larger

- Avalanches will break on deeply buried or basal weak layers

These criteria capture the low-probability/ high-consequence nature of DPS avalanches. A low Likelihood means there will be very few or no natural avalanches, human-triggered avalanches will be unlikely, and large explosive and cornice triggers will only produce some results (ADFAR2). A D3 (Very Large) avalanche could bury and destroy a car, damage a truck, destroy a wood frame house, or break a few trees. When the likelihood slider drops towards “Unlikely” and the size slider climbs to “Very Large or Historic”, we have a DPS avalanche problem (see image below).

DPS avalanches are especially scary because most people don’t have much experience dealing with them. It is hard to gain experience dealing with these beasts because we don’t see DPS avalanche cycles that often. In a typical year we could see over twenty cycles of Storm, Wind, and Persistent Slab avalanches, but we may only see one DPS avalanche cycle in five years. You could navigate through two Storm Slab avalanche cycles in a week of touring, but it could take you ten years to gain the same amount of experience with DPS avalanches. These avalanches are also very large and extremely dangerous. Most people that get caught in one get killed. This makes it very difficult to learn from a close call. Your first encounter with a DPS avalanche could very well be your last.

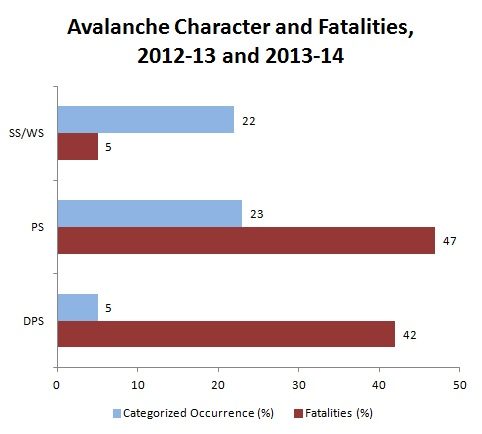

Over the last 15 years, almost all avalanche accidents in Colorado where more than one person died were the result of a DPS avalanche. In two seasons with pronounced DPS avalanche cycles (2008-09 and 2012-13), DPS avalanches accounted for more than 60% of the avalanche fatalities. In the figure below (covering two seasons: 2012-13 and 2013-14) you can see that avalanches involving persistent weak layers are particularly dangerous. DPS avalanches only accounted for 5% of the observed avalanches, but caused 42% of the fatalities. Sure sounds like low-probability/high-consequence, doesn’t it? You can read the whole study here.

In a year with DPS avalanches we can describe the forecast zones where they could happen and the aspect and elevation of the slopes that are most likely to produce one. This is the good news. The bad news is that if you have ten of those slopes, it is really hard to predict which one will produce a DPS avalanche. This is the low probability part. Remember the other half of the description is high consequence. Because DPS avalanches are so dangerous, the only safe way to manage your risk is by avoiding those suspect slopes. On a bad year, you might have to avoid those slopes for the rest of the season. This can be hard to do because people will test suspect slopes, and most will get away with it (they are low-probability events). And due to the nature of a DPS avalanche problem the danger is almost always MODERATE (Level 2) when this is our main avalanche problem, because these avalanches are hard to trigger. That combination -people testing slopes without immediate consequences and a MODERATE (Level 2) rating – doesn’t scream “dangerous” the way an avalanche warning does.

So where are we this year? In some places we can produce D3 avalanches, as demonstrated by the mid-December avalanche cycle. Between December 14 and 21, multiple D3 avalanches released in the Aspen, Gunnison, North San Juan, and Front Range zones. This includes both natural and human-triggered slides. Around half of these avalanches ran naturally during and shortly after the storm cycle. So while we met the size criteria, we weren’t at the point where we called these avalanches stubborn to trigger. Instead, we had Likely to Very Likely, and Large to Very Large PS avalanche problems. This resulted in avalanche warnings and HIGH (Level 4) danger.

The likelihood of triggering PS avalanches in these areas has since decreased, but some notable D3 avalanches released post storm. A narrow escape near Crested Butte, a very large avalanche triggered by a snowcat near Loveland Pass, and explosive triggered slides north of Berthoud Pass, and very large avalanche with an unknown trigger near Cameron Pass have us talking about if a potential DPS problem is in our future.

It is getting harder to trigger an avalanche that breaks into the weak snow near the ground in most of the forecast zones. So the Likelihood of triggering a Persistent Slab avalanche in decreasing. We have seen Very Large (D3) avalanches in the Aspen, Gunnison, North San Juan, and Front Range zones. Most of these zones have a deep enough snowpack to produce more Very Large (D3) avalanches. The Sawatch and Vail/Summit zones picked up less snow during the mid-December storms. Most of the avalanches in these zones have been large enough to kill you (D2), but not large enough to destroy a vehicle or timber structure (D3).We have a basal weak layer, the avalanches are getting harder to trigger, and in some zones they getting quite large. Although we have not started to warn people about DPS avalanches, some of the PS avalanches are getting larger and harder to trigger. The weather over the next couple of weeks will determine if we are just going through a scary period, or if we’ll move into a DPS cycle that lasts the rest of the season. For now, remember that we’ve seen some tricky conditions over the last few weeks and there is no indication they are over. Please read the forecast before you go out and keep in mind that this kind of Moderate (Level 2) danger includes some pretty big avalanches.

Stay safe out there and enjoy the snow! Happy New Year!

Click here to learn more about Avalanche Problems from the USFS National Avalanche Center.